RAINBOW FARM REMEMBERED

- Bobby Black

- Sep 13, 2023

- 17 min read

Twenty-two years ago this month, two gay cannabis activists – Tom Crosslin and Rollie Rohm – were gunned down by police on their property Rainbow Farm in Vandalia, Michigan, after a five-day siege that some refer to as “The Waco of Weed.”

TOM & ROLLIE

Originally from Elkhart, Indiana, Grover Thomas Crosslin loved weed from an early age. Tom (as he preferred to be called) started getting high with his brothers when he was just 14, and cannabis quickly became a normal part of their family life.

“Since the time I was born, there’s never been a time when marijuana was not in front of me,” recalls Tom’s nephew Boss Crosslin Jr. “I remember being at my grandmother’s house for Thanksgiving or Christmas, and my father, Uncle Tom, Uncle Larry, and Aunt Shirley — they’d go out to the garage to smoke before dinner. That was normal to me…that's how I grew up.”

In 1971, Tom Crosslin dropped out of high school and got a job at a car wash. One day, when his boss tried to stiff him for his pay, he extorted what was owed to him using a gun borrowed from a friend — a stunt that earned him a six-month jail sentence. After being released, he briefly joined a bike gang and married one of the female gang members…but broke it off after a couple of years when he realized he was more attracted to men.

Crosslin became a blue-collar jack-of-all-trades and entrepreneur: worked all kinds of jobs, including truck driving, flagpole installation, and even steeple jacking. But what he seemed to most excel at was real estate development — purchasing run-down properties, fixing them up, then selling or renting them out at a profit. At its height, Crosslin’s company owned around 20 properties and employed a crew of around 80 people — mostly divorced or down-and-out guys, some of whom were also gay. After construction jobs, Crosslin would often hold cookouts on the properties—feeding and getting high with his crew. It was through this construction company that he met two of his closest companions, both of whom were also gay: Doug Leinbach, a bank manager who handled fixer-upper properties, who became Crosslin’s dear friend, and an easy-going young crewmember named Rolland “Rollie” Rohm, with whom he fell in love.

When Tom met Rollie in 1990, they quickly connected and began a romantic relationship. Though the two men were very different — Rollie, a slim, quiet, longhaired hippie, and Tom, a burly, bearded hothead nearly 20 years his senior — by most accounts, they complemented each other quite well. Though barely 17 when he met Crosslin in 1990, Rohm had already been married and fathered a son (Robert) with an older woman. Exercising a fatherly influence, Tom introduced Rollie to marijuana (which enabled him to get off the Ritalin he’d been taking for years) and eventually helped him gain full custody of Robert.

BUYING THE FARM

In 1993, Crosslin sold one of his many properties and used the proceeds to purchase an overgrown 34-acre corn farm (and the adjoining 20 acres of woodland) 30 miles north of Elkhart in rural Vandalia, Michigan, for just $35,000 cash. The couple spent many months renovating the dilapidated farmhouse, and within a year, had taken up residence there full time. During one of those long days of working on the house, the couple was relaxing on a hill when a beautiful rainbow appeared in the sky. During that week, they allegedly saw several more rainbows and took it as a sign: they decided to name their property Rainbow Farm.

Crosslin was growing tired of managing all of the properties down in Elkhart and was looking for a way to earn a living there on the farm. Eventually, he got the idea to turn the property into a campground/event center, though where that idea came from varies. According to one account, it came to him after hosting a cookout for over 3200 people on the Fourth of July; according to Boss, however, it was after he and Rollie visited a cannabis venue in Ohio. In any case, Crosslin made the decision to turn Rainbow Farm into “an alternative campground and concert arena" and spent the next few years (and nearly half a million dollars) bringing his dream of a stoner utopia to life.

Appointing Leinbach as Rainbow Farm’s new manager, Crosslin and his team set about transforming the property’s open spaces and overgrown cornfields into one of the top pot destinations in the nation. They drilled a huge well, set up RV hookups, and constructed several structures, including an outdoor stage, a wooden ticketing booth, and a large main building that would house their offices, the Rainbow Farm General Store, “The Joint” coffee bar, the Hemp Gift Store, and a headshop called Smoke World, as well as a game room, a laundromat, and showers for the campers.

“We wanted the farm to be a family campground," Leinbach said. “Most people with alternative lifestyles find it hard to go to a public campground for fear of arrest or harassment by other campers. We were tired of seeing our friends, relatives, and others jailed because of marijuana use. Too many families destroyed, too many tax dollars wasted, just for use of a God-given herb. The sense of injustice grew, and then Tom decided, ‘We're going to throw hemp festivals here.’”

OVER THE RAINBOW

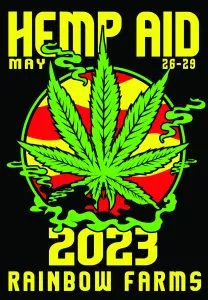

The first event held at Rainbow Farm called simply "Summerfest" (later renamed Roach Roast), took place on Labor Day weekend in 1996 and drew about 200 people. Thus began their tradition of hosting two big annual festivals: "Roach Roast" on Labor Day weekend and "Hemp Aid" on Memorial Day weekend (as well as other various events in between).

Described as “part Woodstock, part union picnic” by Burning Rainbow Farm author Dean Kuipers, these events — which included food, drink, activism, and entertainment — attracted an odd mélange of blue-collar laborers and counterculture warriors, including factory workers, waitresses, hippies, Deadheads, truckers, hillbillies, and activists — all brought together in mutual love and celebration of freedom, peace, and weed.

The legendary Tommy Chong and his family headlined Hemp Aid 99; Big Brother and the Holding Company headlined Roach Roast 2000. In June 2000, they hosted a concert by country music superstar Merle Haggard. And in July 2000, they hosted the High Times World Hemp Expo Extravaganja (WHEE). High Times editor-in-chief Steve Hager became a regular fixture at the events, as well as other prominent activists such as Jack Herer, Michigan icon John Sinclair, hippie guru Stephen Gaskin, famed medical marijuana patient Elvy Musikka, five-time Kentucky gubernatorial candidate Gatewood Galbraith, and Hash Bash organizer Adam Brook.

Thanks to these events, Rainbow Farm became the center of cannabis activism in Michigan—in addition to speeches and voter registration drives, they collected thousands of signatures for the Personal Responsibility Amendment in 2000—a ballot initiative to amend the state constitution to allow adults to grow three mature plants, seedlings and possess three ounces of dried marijuana for personal use.

With each passing year, the events drew more and more attendees — mostly locals, but some from as far as Detroit, Chicago, and even Ohio. At its peak in 1999, Rainbow Farm had nearly 3,000 attendees (not counting the hundred or more volunteers and crew members). Despite their popularity, however, none of these events ever turned a profit; Crosslin had to keep selling off other properties to keep them going, but for him, it was never about the money — it was about creating a safe, free space for people to educate and enjoy themselves. And he succeeded—so much so that in their September 199 issue, High Times named Rainbow Farm one of the Top 25 Pot Spots in the world.

LEGAL HARASSMENT

Unfortunately though, as one might expect, Crosslin’s pro-pot protestivals encountered serious pushback from local law enforcement officials — namely, Cass County’s tough-on-crime conservative prosecutor, Scott Teter. Immediately after being elected in 1996, Teter launched a campaign of litigation and intimidation against Rainbow Farm on a mission to shut it down.

In 1997, Teter filed an injunction against the Farm for violating the county’s “large gathering” ordinance against events with over 500 people, but Crosslin outsmarted him by registering the Farm as a legal non-profit organization through the 420-friendly Columbus Institute of Contemporary Journalism. The following year, Teter tried to shut down their event for not having a campground license…but a clerk at the courthouse who was sympathetic to Crosslin’s situation issued him a temporary license practically overnight, thus thwarting Teter’s efforts again. And in 1999, Teter claimed that Rainbow Farm had lost its 501(c)(3) status and would need to reapply or face a lawsuit, but again his efforts were thwarted when it was determined that a clerical error was to blame — one that was quickly corrected.

Unable to stop the events through the courts, Teter set up a drug task force devoted entirely to Rainbow Farm. They set up police checkpoints on the roads leading into and out of the farm to stop, question, and presumably search vehicles of festival attendees — a move that kept many locals away for fear their license plates were being recorded for future harassment.

Teter also sent a cadre of narcs into the event to make drug busts. Though they were able to purchase some drugs from individuals there — various pills, coke, and LSD — they were never able to tie Crosslin or his employees to anything illegal. Nevertheless, in March 1999, Teter sent Crosslin a letter stating that he had evidence of drug sales on the property and that as soon as he could link Crosslin to them, he would take the farm away from him (under the Drug War’s civil forfeiture laws). The threat of losing his land infuriated Crosslin, prompting a heated and foreboding reply:

“I have discussd this with my family and we are all prepared to die on this land before we allow it to be stolen from us,” Crosslin wrote. “How should we be prepared to die? Are you planning to burn us out like they did in Waco, or will you have snipers shoot us through our windows like the Weavers at Ruby Ridge? [...] [You will] have the blood of a government massacre on your hands.”

RAID & REBELLION

Ironically, the beginning of the end for Rainbow Farm started on 4/20 in 2001.

On the morning of April 21, a 17-year-old named Konrad Hornack — who was still wearing a wristband from the 4/20 event held at the Farm the day before — crashed his car into a school bus full of kids. Thankfully, none of the students were seriously injured, but the driver himself was killed. Police reported that he had marijuana in his bloodstream, though his friend said they hadn't smoked for eight hours prior to the crash and that he wasn't under the influence. Regardless, Teter blamed Rainbow Farm for the accident and capitalized on the negative publicity to finally make his move against the Farm.

A few weeks later, in the pre-dawn hours of May 9, around 30 state troopers in tactical gear raided Rainbow Farm — waking those inside by pointing guns in their faces (a measure Teter justified with the threats of Crosslin’s angry letter two years earlier). Their search warrant wasn't for drugs, but for payroll records related to a trumped-up tax fraud charge. Apparently, some woman who’d worked at The Joint had turned informant and told Teter that Crosslin was paying his employees off the books. Teter had forwarded that information to Michigan’s Treasury Department, which had a warrant issued to search for “financial and accounting records from 1998 to present including all payrolls records.”

“They never even bothered to call Rainbow Farms to ask them about it before they raided them,” Boss says. “They were joking about the whole thing from the beginning. It’s all in the dispatch reports. ‘Did you call? No, I didn’t call…should we call? We don't know.’ They were already staging [the raid] at this point, and nobody had even bothered to call to ask what was going on.”

Once inside the farmhouse, police allegedly found over 300 young cannabis plants (just three inches tall) in the basement. (With no one willing to sell them weed due to the heightened scrutiny around the farm, Tom and Rollie had built themselves a small hydroponic grow room). They also found three loaded firearms, which Crosslin wasn’t permitted to own due to his past gun conviction. Tom and Rollie were both arrested and charged with felony cultivation, possession, and weapons charges, as well as running a "drug house." Altogether, Tom was facing up to 20 years in prison.

But that was just the beginning: the day after their arrest, the court issued an injunction banning any more events on the property. Also, by the time the couple had gotten out on bail, Teter had already filed an 18-page complaint detailing whatever evidence of drug sales he had and requesting to seize the farm under the drug asset forfeiture laws. And cruelest of all, on May 15, Teter also had the couples’ son Robert, who was now 12 years old, taken away by Child Protective Services and placed in foster care — claiming he was a victim of “neglect and abuse.”

Despite everything they were facing, or perhaps because of it, Crosslin apparently announced on the website that they’d be going forward with their annual Labor Day party, as well as another small event on August 17 — both in obvious defiance of the court order. Apparently, only a few dozen people showed up to the gathering on the 17th, but two of those people were undercover cops, who reported back that Tom had offered them hits from his pipe. This prompted Teter to petition to have the couple’s bail revoked, and a hearing was scheduled for August 31.

The end was drawing near for Tom, Rollie, and Rainbow Farm, and Tom apparently knew it – confessing to Leinbach: “I’m going to die on my farm, not in prison.” During the last week of August, both Tom and Rollie composed handwritten wills (leaving all of their possessions to Robert), then started giving away stuff from the Farm's shops to whoever was there that wanted it. Tom also left a note in an old house he was renovating in downtown Vandalia that read in part:

"The action we must take now is not what we wanted. We would have preferred a peaceful end to the drug war … No longer are we talking peace. The Government must be stopped. Scott Teter knew what was coming … Our police no longer serve and protect us. We need protection from people [sic] we hired to protect us ... Let the battle begin."

UNDER SIEGE

When Friday, August 31 arrived, Tom and Rollie never showed up in court for their hearing. Instead, early that morning, they went around the property asking all of the campers to leave.

"Get the hell out of here," Crosslin reportedly told them, "and don't you dare come back — just watch the news tonight."

He then began setting fire to the farm’s structures that he’d spent so much money and effort to build. If the government was going to seize his land, Crosslin reasoned to friends, he'd “make sure there was nothing left on it.” Seeing smoke, some neighbors called 911 to report the fires. But police, claiming they had received an anonymous tip that the fires were a trap, kept all emergency responders on the outskirts.

Thus began the five-day, Waco-style siege of Rainbow Farm.

At around noon, a local WNDU-TV news chopper flew overhead to get footage of the fires, and Tom — probably thinking it was a police copter, since it was blue and white — allegedly shot at it and hit it a few times before it flew off. However, Boss suspects that it was no innocent news chopper — rather, he believes it was actually running recon for the cops.

"They've got a station set up three or four miles down the road from Rainbow Farm, so why would they allow a news helicopter to fly over land that they're not even willing to drive in to check out?"

Boss also doesn't believe that it was his uncle who shot the chopper, but rather someone else (perhaps Rollie?) that he was covering for by taking responsibility for it.

"I believe somebody else shot the helicopter," he attests. "I'm not gonna say the name, but I know my uncle's shot was not that good."

Nevertheless, since shooting at a helicopter is a federal crime, the FBI was then called in, along with SWAT teams, helicopters, surveillance planes, and light-armored vehicles (LAVs), all of which surrounded the property.

Over the next few days, Tom and Rollie continued burning down structures until the only building left standing that remained was the farmhouse where Tom and Rollie were hunkered down. Meanwhile, locals who supported Rainbow Farm gathered along the road outside the property to protest what law enforcement was doing to Crosslin and his crew.

Buggy Brown, a neighbor whose home authorities had commandeered as their field HQ, was reportedly coming in and out of the Farm bringing them food and saying that they seemed calm—just "watching TV, taking showers, and smoking weed." (Boss also suspects Brown was providing intel to the cops).

On Sunday, September 2, state troopers reportedly brought in some of Tom’s family members, friends, and attorneys, and tried to send in a cell phone, all in an attempt to negotiate. But Crosslin didn't want to talk to the cops. In fact, when they tried to speak to him over loudspeakers they’d set up, someone in the house allegedly shot at the speakers. Crosslin also allegedly fired at the police planes and choppers, and even sprayed shots into the woods to deter them from getting too close. As a result, that night, three FBI sniper teams in camouflage set up a perimeter around the property, lying in hiding in the woods to monitor the house.

LABOR DAY MASSACRE

On Monday, September 3, Crosslin finally agreed to speak with police on a phone brought in by Brown. He asked to speak with the media, and with Robert, but police refused his requests, so he cursed at them and hung up. Later that afternoon, Crosslin, armed with a rifle, walked out towards the edge of the property with a young man named Brandon Peoples — an unfamiliar character who had somehow mysteriously managed to sneak past the police barricades and onto the property for some reason.

"I never met this guy. I have no clue who he is ... everybody at Rainbow Farm really had no clue who he was," Boss tells us. "Now he sneaks in on the property, and he's suddenly here during the standoff, supposedly supporting my uncle Tom and Rollie."

Though it's reported that Crosslin left to go retrieve supplies from a neighbor's house, Boss believes the main reason he ventured out was to escort Peoples off the farm. In any case, he did, in fact, stop at his neighbor Butchie's house, where he picked up a coffee pot and a few other small items. After leaving the neighbor's, Crosslin reportedly heard a noise and spotted one of the FBI snipers lying on the ground by some debris. He then allegedly raised his rifle, at which point two snipers opened fire — hitting him in the head and killing him instantly. (The autopsy report later stated that Crosslin was shot five times in the head and three times in the torso.)

The official police report also states that Peoples, who was directly behind Crosslin, didn't see anything because he was conveniently "bent down tying his shoe" when Crosslin was shot. This sounds very fishy, says Boss, considering that hospital reports show Peoples had fragments of Crosslin's brain and skull cleaned out of his eyes — which would have been near impossible if he was bent down given the positions of Crosslin and the sniper. All of which begs the question: Was Peoples, a total stranger who'd inexplicably arrived on the Farm during the standoff, actually a plant sent in by authorities to lure Crosslin out into the open so he could be targeted for execution?

What's more, Boss is in possession of reports that clearly state that Tom was speaking to Rollie on a walkie-talkie just before he was shot — pointing out that if Tom was holding a coffee pot in one hand and speaking with Rollie via walkie-talkie with the other, then he couldn’t have been aiming a rifle at the agent.

“Before that gunshot rings out, it's in the report that Tom radios to Rollie, ‘Incoming!’ Boss explains. "So if he had his hands full with a walkie-talkie and a coffee pot, that means Tom never pointed a gun—the rifle was on a strap across his back!”

In fact, it was that very blood-splattered walkie-talkie that the FBI then used to call Rohm (now alone in the farmhouse) and tell him his partner had been killed.

After hearing of Tom's death, Rohm agreed to accept a telephone. State police drove up toward the house in one of the LAVs and tossed a phone at the porch, which he then retrieved. They maintained a dialogue with him into the night until just after 3 a.m. when he presumably fell asleep — at which point the cops apparently thought it would be a good idea to “wake [Rohm] up” by firing a few "dummy rounds” through the windows. Initially, police claimed these were just rubber baton rounds, but some reports state that they also fired a flashbang grenade at around 4:00 a.m. In any case, Rohm resumed negotiations and agreed to surrender at 7 a.m. on one condition: that his son be brought to the farm so he could see him and say goodbye before being taken into custody — terms which police agreed to. But that peaceful resolution to the standoff was about to go down in flames — literally.

Around 6 a.m., police reported that the second floor of the farmhouse had somehow caught fire. Half an hour later, Rohm emerged from the house (presumably to escape the smoke and flames), dressed in fatigues and allegedly holding a rifle. The LAV, nearly 200 yards away, began to approach him. Through the smoke, police claimed to see him pointing a rifle toward them, at which point two of the officers fired several rounds at Rohm, one of which went right through the stock of his rifle and hit him in the chest. Despite having an ambulance sitting at the ready just outside the farm, Boss claims that police allowed him to lie on the ground for over 40 minutes and bleed to death.

Tom Crosslin was 46 years old when he was killed ... Rollie Rohm was just 28.

AFTERMATH & LEGACY

Given his rhetoric leading up to the siege, it seems clear that Tom’s intention all along was to be killed — suicide by cop, as they call it these days. But there’s little reason to believe that Rollie had a death wish as well: he’d already agreed to turn himself in and only left the house before the agreed-upon time because it was on fire. So while the official reports blamed Rollie for the blaze — supposing he was finishing what Tom had started — friends and family accuse police of starting the fire themselves (with the flash grenade) to flush Rollie out specifically so they could kill him. As a matter of fact, Rohm's family filed a wrongful death civil lawsuit against Michigan State Police in 2003, alleging just that.

“Rollie was straight-up fucking murdered!" Boss contends. "They burned the house down to get him out, and when he came out, they shot him. To be honest with you, I don't think he even had a gun in his hand. They wouldn't allow him to surrender, because if Rollie was able to tell my family that Tom was murdered while talking to him on a walkie-talkie, then they couldn't take this land and do what they did. They had to kill Tom and Rollie to be able to take this land.”

Unfortunately, the story of Rainbow Farm never got the national press it deserved since the terror attacks of 9/11 happened one week later – eclipsing all other news stories for many months after. (Ironically, some people have suggested that if the FBI had spent more time and resources on trying to protect America rather than on trying to bust cannabis users, perhaps 9/11 could have been prevented.)

So what happened to Rainbow Farm after Tom and Rollie’s deaths? Instead of going to their son Robert as the couple intended, it was confiscated, broken up into six parcels, and auctioned off to different buyers with the stipulation that they couldn’t turn the land into campgrounds or throw events there — Teter's attempt to prevent Robert or any other potential owners from memorializing Tom & Rollie or continuing their work in the future. Thankfully, those efforts failed: in 2012, after changing hands several times, the property was purchased by a farmer/engineer named Gary Healy, who has since renovated the land and reopened it as the New Rainbow Farm.

A wooden cross now stands atop the hill where Tom Crosslin was shot, as well as one by the pine trees where Rollie was killed, and a third larger cross to commemorate them both, alongside benches for visitors to sit and reflect.

"People can just walk up there, and if they feel like they wanna smoke with my Uncle Tom, they can smoke with my Uncle Tom," says Boss. "You guys wanna go smoke with Rollie? You guys go down there and smoke with Rollie."

Though Tom and Rollie are now honored with memorial sites on the property, the greatest tribute to their courageous lives is the continuation of their legacy: Rainbow Farm is once again hosting 420-friendly concerts and festivals — with Rollie's son Robert running sound for the stage, and Boss Crosslin promoting the events and giving educational tours.

“We're trying to breathe life back into the Farm so that we can get what really happened here out to people. That was the main objective of starting this thing back up,” Boss attests. "Anybody can come to Rainbow Farm asking for Boss, and I'll take them on the grand tour and explain that history to them.”

What's more, today's events even feature "caretaker" vendors selling cannabis that – thanks in part to Tom and Rollie's sacrifices – is now legal in the state of Michigan.

“Thinking of my uncle up there looking down and seeing it being done now on his land ... something he was fighting for ... that's the best feeling of all."

COLLECTION ITEMS:

[1] Hemp Aid '99 staff t-shirt; 1999; Item #C091

[2] Hemp Aid 2000 poster; Artist: Steve Marcus; 2000; Item #P045

[3] Merle Haggard concert handbill; 2000; Item #F013

[4] Assortment of Hemp Aid '99 colored handbills; 1999; Item #F012

[5] Personal Responsibility Amendment 2000 initiative promo sticker; 2000; Item #C006

[6] Rainbow Farm branded rolling papers; 2000; Item #S007

[7] Rainbow Farm event map; 1999; Item #D003

[8] Assortment of Boss Crosslin's Rainbow Farm event laminates; 1997-2001; Items #C092

[9] Rainbow Farm branded water bottle; 1999; Item #C094

[10] Branded soil sample from Rainbow Farm; 1999; Item #C004

[11] Original "We Support Rainbow Farm" protest sign; 2001; Item #P045

留言