PUFFING UP THE PROTO PIPE

- Bobby Black

- Oct 1, 2024

- 13 min read

Updated: Dec 1, 2024

When it comes to stoner tech, it doesn’t get more historic than the Proto Pipe. Often referred to as the “Swiss Army Knife of paraphernalia,” the Proto Pipe was essentially the first smoking device explicitly designed with the cannabis consumer in mind.

EARLY INSPIRATION

The Proto Pipe is the brainchild of an artist and self-taught machinist from Denver named Phil Jergenson.

“As kids, we started building model plastic cars, and then the new thing was slot cars,” remembers Phil’s brother Richard Jergenson. “All of a sudden, we were able to put a motor in them and race our friends. That's where we learned how to solder and fuse metal together, which later became instrumental in birthing the Proto Pipe.”

As a teenager in the late 1960s, Phil got turned on to cannabis after a neighbor of his visited San Francisco.

“When he came back, he brought some weed with him… and like a good neighbor, he turned on my brother,” says Richard. “Phil just loved it. He was an artist, and it got his creative juices going … allowed him to suspend time and just do the magic that this amazing plant allows us to do.”

Richard’s initiation into the stoner lifestyle came soon after his brother’s — in December 1968, under the most epic of circumstances: just before seeing Led Zeppelin play their first-ever US show at the Auditorium Arena opening for Spirit and Vanilla Fudge when he was 17.

It was just a few months after getting high for the first time, while riding a ski lift, that Phil had what he calls his “eureka moment.”

“I was trying to light a pipe that I’d made out of cardboard and the lid to an old film tin [as] the bowl,” he told the LA Times in 2021. “And I just realized I didn’t have any of the implements that you needed. That’s when I decided I was going to design a pipe.”

THE PIPE DREAM

Part of the reason that Jergenson was inspired to invent a new pipe in the late 1960s is that there weren't really any pipes available that were targeted to weed smokers. At that time, there were only tobacco pipes made of corn cobs, carved stone or wood, or cheap, screwed-together metal components. With the space race, innovative new home appliances, and James Bond dominating the media landscape, Jergenson sought to make a pipe as cool and futuristic as possible. And as a stoner who earned his living drafting and building detailed models for an architectural firm, Jergenson was the ideal candidate to do so.

“Gadgets were in,” he explains on his website. “James Bond had them … how about one for us? How about a special pipe designed to do only one thing perfectly: smoke!”

To bring his literal pipe dream to life, Jergenson spent weeks designing what would eventually become his life’s work. He bought himself a versatile Swiss tabletop machining device called the Unimat and started pumping out prototypes. At first, he used aluminum, but soon realized it didn't dissipate the heat quickly enough, creating a danger of burning your lips. Then, remembering the slot cars of his youth, he shifted gears to brass, which solved the problem.

With each new iteration, he added more built-in tools and features, such as a permanent screen, a swivel bowl lid, a tamper, a steel-tipped poker, a cleanable resin trap, and a storage pod to keep your “combustibles” in. Finally, after countless late-night hours at the machine, he’d come up with a device he was satisfied with: the first high-end pipe designed specifically for cannabis users, which he called — for lack of a better term — The Contrivance.

PROTO PIPE TAKES OFF

With a cool new product to sell, all he needed now was to connect with his market. And so, in 1970, Phil Jergenson (and his brother Kent) left the deep red military state of Colorado and headed out to the counterculture capital of San Francisco to find his fortune. There, Phil secured an 800-square-foot warehouse in the Mission District for $65 a month and began teaching himself to upscale production. Once the shop was up and running, Phil summoned their other brother Richard, who quit his job as a casket builder and followed them out there to help get their pipe dream off the ground.

“San Francisco was the epicenter for the growing youth movement,” Richard posits, “and to me, cannabis seemed to be the glue that helped hold the movement together.”

The brothers began cranking out pipes and selling them to hippies on the street for five dollars apiece. But things got off to a rocky start: the drill press on their machine wasn’t creating precise enough holes, causing most of the pipes in their first batches to be defective — which, in turn, meant they didn’t earn enough in sales to cover their expenses.

“Christmas was coming, and we'd lost our opportunity because we had far more rejects than we had product to sell,” Richard recalls. “So we had to all go out and get day jobs to help subsidize continuing the dream.”

For Phil, that, unfortunately, meant moving to Fullerton in Southern California to work a carpentry gig. After a year or so of lackluster results, he feared his beloved pipe dream was in danger of going up in smoke. Then, in June 1972, he took a gamble and spent $120 to place a tiny ad in an up-and-coming magazine based in the Bay called Rolling Stone. At first, he thought it had been a waste of money since, in the first several weeks after the ad ran, they only had a few inquiries. But a couple of months later, Kent called to tell him that their post office box was overflowing with orders. The boys had found their market. But with Phil living down in Fullerton, he had to take redeye commuter flights back up to the Bay to make pipes on weekends. It would take nearly a year of rerunning their ad and filling orders on weekends before they’d earn enough for Phil to quit his day job, move back to San Fran and make pipes full-time.

Before long, the brothers were selling pipes like hotcakes — Phil at Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley, and Richard at Fishman's Wharf in San Francisco. They each had a portable walnut burl and brass table that they would set up on the street — a curiosity that would lure in potential customers passing by.

“[The table] would stop a lot of people, just the presence of this booth. And then they’d go, ‘Well, what is this?’ And then they'd see the pipe.” Richard explains. “Every pipe that was made, we would sell out by day’s end. We always came home with an empty bag and an incentive to get up in the morning and do it again.”

By 1973, business was so good that they were able to upgrade their operations — opening a second shop (a 25,000-square-foot warehouse) on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley. But the real game changer came in the fall of 1974, with the premiere of a new magazine focused entirely on marijuana culture—High Times. The Jergensons placed their first ad for the Contrivance in the Spring 1975 issue of HT, and it performed so well that they continued to advertise in the mag on and off for almost a decade.

RIPOFF & REBRANDING

One day in 1975, while Phil was selling pipes on Telegraph Avenue, he was approached with a proposition by a fast-talking guy calling himself Israel Juda, who purported to be a record promoter from SoCal. During a meeting at a nearby Chinese restaurant, he flashed Phil a briefcase full of cash (supposedly $100,000) and made him a dubious offer:

“He said, ‘Look— this is going to go one of several ways,” Richard recounts. “You're either going to sell me the business for $30,000, or we're going to be business partners fifty-fifty, or I'm going to make these in India without you.”

Even odder, he had a wacky, Andy Warhol-inspired gimmick in mind to help sell the pipes.

“I'm going to call them The Tomato,” he pitched. “We're going to etch the name ‘Tomato’ on the top of the pipe, and we're going to put 'em in a can with a tomato label on it. And that's the marketing shtick.”

Thinking it would be better to utilize his investment money rather than be ripped off, Phil agreed to bring him on as a partner and gave him 50 units to help market the pipe. Within days, a giant pallet containing 10,000 cans (which he’d evidently scammed from the American Can Company) showed up at their warehouse. But after Richard met him and talked it over with his brother, they decided to back out of the deal.

“The more we saw this guy, the less we liked him,” Richard says. “So we said ‘take your cans and get out of here.’ There was an altercation — Phil was taking pictures, as we were trying to find out who he really was, when he jumped Phil to get at the camera. A scuffle ensued, but the photos were intact. But he took the cans, and he left.”

Sure enough, about a month later, tomato cans containing forgeries of the Contrivance began showing up in headshops and record stores all around the Bay Area. He’d taken their pipe to a machine shop and had them recreate it using cheaper materials.

“I was so pissed off,” Richard says. “But oddly enough, it helped us get our stuff together.”

To counteract the new knockoffs on the market, in 1976, the Jergensons took several significant steps — the first of which was changing the product’s name.

“'Tomato’”! What a stupid gimmick idea!” Phil writes on their website. “But it did wake me up to the fact that the name Contrivance was also pretty stupid.”

While discussing the pipe with Phil one night, a friend of theirs who meant to say “prototype pipe” mistakenly referred to it as a “proto pipe,” and the name instantly stuck. They registered the name, then solidified the new moniker by etching a pair of interlocking “P” s (inspired by the Rolls-Royce logo) onto the lids of all of the new Proto Pipes they produced.

Next came stage two: convincing shop owners to carry their official Proto Pipes rather than the knockoffs.

“I would go to these shops and ask for a Proto Pipe, and of course, they didn't have them because we were new to the game with that name,” says Richard. “And they'd say, ‘Well, we don't have that, but this is what we do have.’ And I would disassemble it right there in front of them and hand them back a pile of parts and say, ‘Well, this isn't a ProtoPipe.’ Then, the next day, Phil would show up with a bag of pipes and a counter display. Every shop that we went in got rid of the ‘Tomatoes’ and started selling the Proto Pipe.”

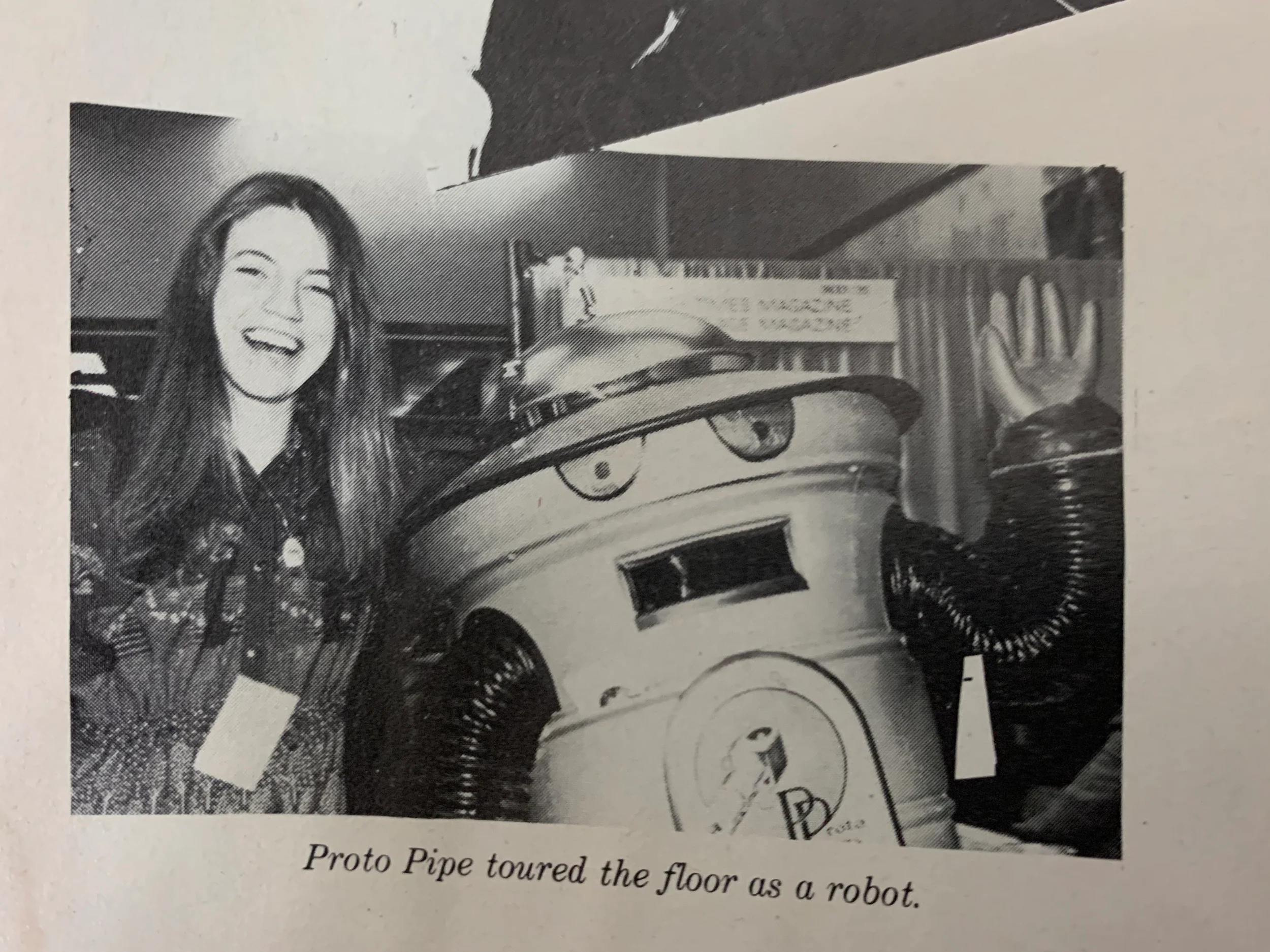

The final step of their relaunch consisted of bringing in some new, more trustworthy partners— including high school buddy Dave Leverett and a talented underground cartoonist named Larry Todd. Todd, who had made a name for himself in the Bay Area stoner scene with his Dr. Atomic comics, helped them rebrand the Protopipe by drawing up fun new ads for them and even lending them one of his comic characters to use as their mascot: a trash can-shaped robot which they renamed “Probot.”

“Larry gifted us Robot, and it became Probot — our iconic mascot,” says Richard. “Probot always was different from ad to ad — sometimes he was a rocket, sometimes he had legs, sometimes he had tractor tires … but it was always Probot in the ads pitching the pipe.”

The partners even made a life-size Probot costume to promote at trade shows (which they still have today). In fact, when they shared a booth with Paraphernalia Magazine at the New York Fashion and Boutique Show at the Jacob Javits Center in the winter of 1979, Probot became the hit of the show.

“Our timing was perfect because Star Wars had recently come out. Everybody was saying, ‘Oh my God — it's R2D2! And we were like, ‘No, it's Probot!”

MOVE TO MENDO

By this time, the partners had successfully outmaneuvered the conman’s counterfeit contrivances … but unfortunately, they faced new challenges on their horizon.

In 1979, their warehouse in Berkeley was sold to a new owner, who decided to double their rent overnight. Since the Jergensons already owned a 40-acre property in the small Mendocino town of Willits, they decided to move their operations there—taking over a former car dealership garage space downtown, then buying a one-acre property next door with several buildings on it, which they began remodeling. But apparently, the city council wasn’t too happy with them being there, despite the fact that everyone knew the town’s economy was cannabis-driven.

“We were the only visible tip of the underground economy, which is what was keeping Willetts and Ukiah and Garberville and all these communities in Northern California alive for decades,” Richard explains. “We weren't out in the hills— we had a storefront on Franklin Ave, smack dab in the middle of downtown Willits. So we had to be squeaky clean because all eyes were on us. It was a political hotbed — we had to create a petition and go out and get hundreds of signatures from locals saying, ‘We want this business to stay here.’ But we were harassed, so we ended up moving to another side of town to get away from that.”

DRUG WAR DOWNER

By the mid-1980s, Proto Pipe was riding high — employing around a dozen staffers and churning out nearly 500 pipes a week. But in Ronald Reagan’s Drug War America, that success came with a healthy fear of being busted — especially after the passage of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, which, among other things, banned the interstate sales and transportation of drug paraphernalia.

“Paraphernalia … that was the demon word,” Richard laments. “I mean, that new law felt like it was being targeted at us. So we were trying to rebrand as smoking or lifestyle accessories … any way of changing and controlling the dialogue. But ultimately, we just didn't want to go to prison.”

Hoping to avoid becoming the poster child for Reagan’s draconian new law, and believing that legalization was likely right around the corner, the brothers decided to play it safe: in the winter of 1987, they sold the business at a significantly reduced price to a friend named Michael Lightrain who was willing to run it for them temporarily, with the understanding that whenever legalization came about, they could buy it back. Rebranding it as a tobacco pipe, this new owner then ran the company successfully for over two decades.

Meanwhile, the Jergenson brothers moved on to other pursuits: founding a company called Grid Beam that allowed people to easily design and build their own furniture using a “life-sized Erector set” that Phil invented. Richard also devoted more time and energy to his other passion: being a cannthropologist. Over the years, he’d curated a vast collection of counterculture memorabilia and artifacts, including clothing, posters, books, magazines, and thousands of newspapers showing the timeline from pre-prohibition through prohibition.

“I'm not a world traveler, but I spent almost 10 years in the Bay Area,” he says. “I was part of the culture — I frequented all of the bookstores and all the shops, and I didn't get rid of things as they entered my gravity field. I would just snag things along the way and put 'em aside for another day.”

It was this impressive archive that would eventually inspire the Jergenson brothers to reclaim the brand they’d built.

REUNION & RECLAMATION

Fast forward to 2014: After surviving a battle with cancer, Richard was reexamining what he wanted to do with the rest of his life.

“I’ve got this astonishing archive of counterculture material,” he thought. “Why not do something with it?”

Richard contacted Emerald Cup organizers Tim and Taylor Blake, who, after visiting him and seeing his collection, offered him a space at the event that December.

“I invited Phil and Larry, so it was the three horsemen back together again after three decades,” Richard recalls. “We had a great showing. The reception was just fantastic.”

Impressed by how legit the cannabis community had become, the partners were inspired to get back in the game. The only problem was that Lightrain was less than cooperative.

“We had an agreement that when legalization came, we wanted the business back. However, when that day came, the agreement was not honored,” he says.

Unable to regain control of their company as promised, Phil decided to move forward without the Proto Pipe name. He got to work redesigning his device for a new generation: making the bowl larger and round instead of oblong, and adding a swivel lid to the bottom trap and top bowl clip. He named his new contrivance the Mendo Pipe and began manufacturing and selling them from his home — competing with the original pipe he’d created as well as various Chinese knockoffs on the market.

But Lightrain’s mismanagement of the company would soon work in the brothers’ favor.

“He ultimately drove the business into the ground because he was an absentee owner and was never really a part of the culture,” Richard says.

As a result, the company fell into debt, and by 2017, Lightrain was so far behind on the warehouse’s rent that the landlord — who the Jergensons had always had a great relationship with — took him to court and got him evicted. Since the brothers had supported the landlord during the lawsuit, he offered them their old space on Franklin Ave back.

“He’d left all of his booty and junk behind, so there was 4,000 square feet of stuff to sort through and to clean up.”

What’s more, he’d also let the trademark and patent lapse, enabling the brothers to reclaim them. So, after 30 years, the Jergenson boys finally were back in control of the brand they’d built.

THE SHAPE OF THINGS TO COME

Since regaining their company, the Jergensons have been rejuvenating the brand one step at a time. First, they rebranded the Mendo Pipe as the Proto Pipe Rocket. Next, they enlisted Phil’s daughter Rona (who’d recently graduated from college) to build them a website — enabling stoners around the world to access their products and drawing some much-needed attention to the brand.

“Rona created this website, and that was the game changer,” Rich professes. “All of a sudden, a journalist from the LA Times caught wind of it and reached out… he wanted to do a story because it was his first pipe and he really bonded with it. Nine months later, [the LA Times] sent him and three videographers to Willits to get the story. And when the article came out in October 2021, it was a full page in the LA Times and our website crashed!”

Since the launch of their website, consumer sales for the Proto Pipe have skyrocketed — flipping from 95% wholesale before to 95% retail after. Today, they produce about 1000 pipes a month and, to date, have sold more than 1.5 million units worldwide.

“The numbers aren't quite what they were back in the real heady days,” Richard admits. “But the quality of the pipes is off the charts. And everyone is so happy that the founders are back.”

Safe to say, we can count that LA Times reporter, Adam Tschorn, among them:

“In many ways, [Proto Pipe is] the Levi Strauss of cannabis.” he wrote. "It’s a legacy brand that has roots in — and an authentic connection to — the earliest years of America’s great weed awakening of the 1970s. That’s a rarity shared by only a few others in the space today, including stoner comedians Cheech and Chong and High Times magazine.”

As the company’s official archivist and historian, Richard is currently working on a book that will tell the whole story behind Proto Pipe’s storied stoner history … one that, as a fellow cannthropologist, I look forward to reading someday.

For more on the Proto Pipe, visit their website at protopipellc.com

Comments