THE LIFE & LEGEND OF JOHN SINCLAIR

- Bobby Black

- May 31, 2024

- 16 min read

Updated: Oct 2, 2024

This April, the cannabis movement lost one of its founding fathers with the passing of the “Hippie King of Michigan,” John Sinclair.

ORIGIN OF AN ACTIVIST

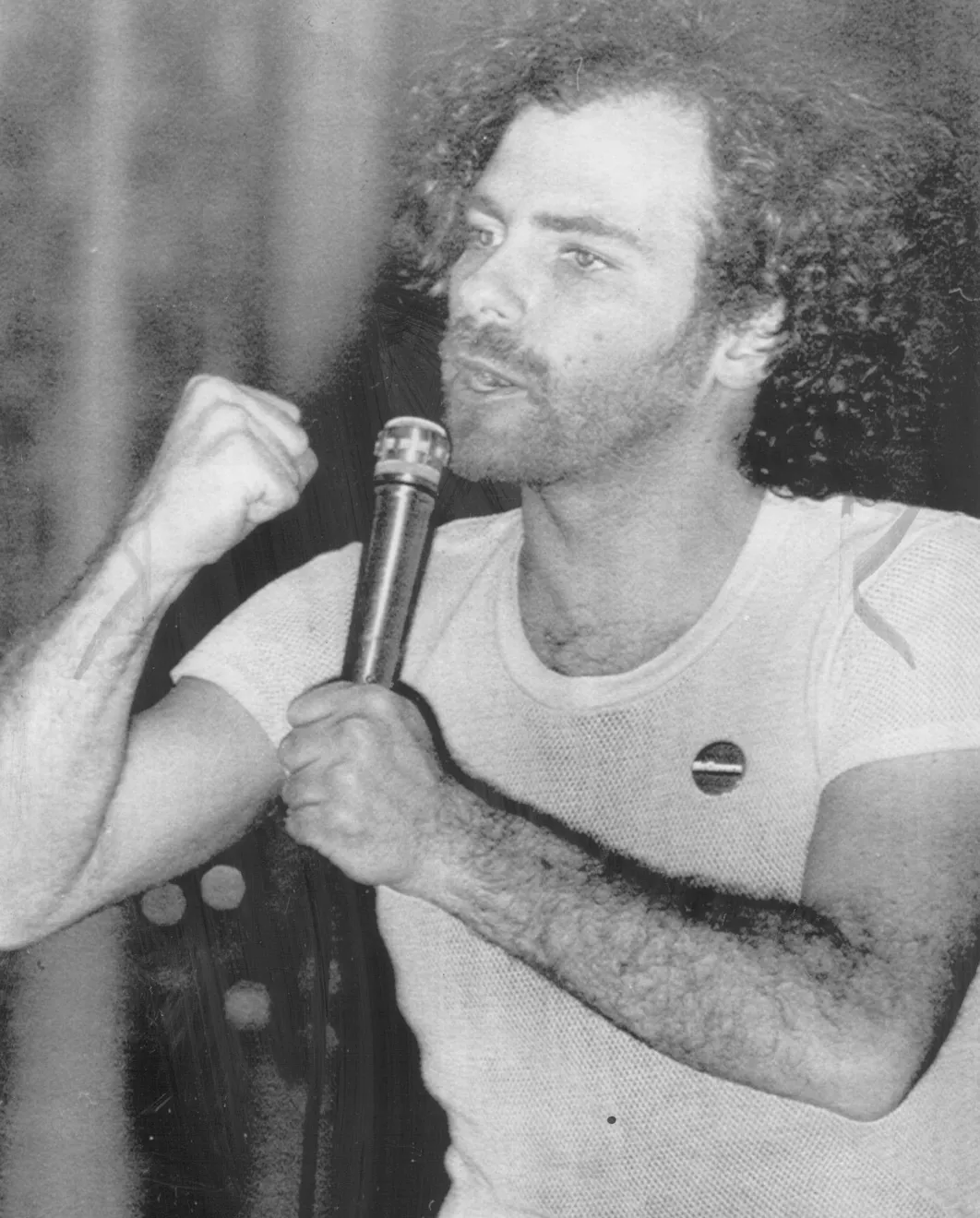

When it comes to marijuana activists and advocates, beatnik badass John Sinclair was as OG as they come.

Growing up in a middle-class Republican household in a small town called Davison outside Flint, Michigan, Sinclair first turned on to Beatnik culture in 1959 while attending Albion College in 1959. He went on to attend graduate school at Wayne State University in Detroit, where he wrote his Master’s Thesis on William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch and met a girl named Magdalene "Leni" Arndt—the German artist/photographer who, a few years later, would become his wife.

Through his love of jazz, poetry, and marijuana, Sinclair quickly ingratiated himself into Motor City’s bohemian leftist community.

On October 7, 1964, Sinclair was arrested for selling $10 of weed to an undercover state police officer. Originally charged with the sale of narcotics, he pleaded guilty to the lesser charge of possession and was sentenced to two years’ probation.

Less than a month after his arrest, he dropped out of college and co-founded both the Detroit Artists Workshop, which hosted a series of cultural events, and the Artists’ Workshop Press, which produced numerous underground publications. Then, in January 1965, he founded Detroit LEMAR (LEgalize MARijuana), a Michigan chapter of the nation’s first cannabis advocacy group that had recently been created in New York by the Yippies.

"I got a flyer in the mail from New York from my fellow poets Ed Sanders and Allen Ginsberg where they announced the formation of New York LEMAR and the first marijuana demonstration," says Sinclair. "I thought, what a great idea ... we ought to do this in Detroit. So we did.”

As the head of Detroit LEMAR, Sinclair used the DAW and AWP to organize meetings and publish pamphlets in support of cannabis—and, in so doing, established himself as one of the true founding fathers of the legalization movement. Of course, being the public spokesperson for an illegal “narcotic” also drew a target on his back.

In August 1965, Sinclair was again arrested—this time by Detroit Police for “procuring a small bag of marijuana” for an undercover narcotics agent. Though he sought to challenge the constitutionality of the state’s marijuana laws, he was unable to find a lawyer who would take the case and was forced to once again plead guilty to possession. As a result, in February 1966, he was sentenced to another two years of probation, as well as six months in the Detroit House of Correction. Rather than be deterred by his incarceration, however, Sinclair only became more determined in his activist efforts.

“I was an agitator and started the legalization of marijuana and was very public about my beliefs,” Sinclair explained in a 2011 interview with therumpus.net. “So they thought, ‘let’s show these young people they can’t get away with this.’ So I was the anti-symbol: ‘We must take them on’ was my motto.”

TRANS-LOVE ENERGIES

After his release from DeHoCo in August 1966, Sinclair got to work on his next project: with the help of his wife Leni, MC5 singer Rob Tyner, psychedelic poster artist Gary Grimshaw, and a new friend named Lawrence Robert "Pun" Plamondon, the DAW was expanded into a new counterculture collective/commune they dubbed Trans-Love Energies (a name they derived from a Donovan song).

In addition to their previous artistic and educational endeavors, the group now planned to offer fellow hippies housing, transportation, and even access to a legal defense fund. To bankroll these efforts, TLE planned several concerts and events, the first of which was “Guerrilla Love Fare” — a huge concert at the Grande Ballroom scheduled for January 29th, 1967. Unfortunately, less than a week before the event, police intervened to stop it.

Just before dawn on January 24, more than two dozen officers raided the Plum Street commune (nicknamed "The Castle") as part of a four-month-long undercover sting operation. Apparently, a month earlier, on December 22, an undercover female narcotics agent who’d infiltrated the group had persuaded Sinclair to give (not sell) her two joints—for that, he was being accused of being the ringleader of a “massive campus dope ring.”

Of the 56 people arrested that morning, only fourteen were charged, including, of course, John and his wife Leni (who reportedly was roughed up despite being visibly pregnant). Leni’s case was later dismissed on a technicality, and the rest pleaded guilty on minor charges and got off without any jail time…John, however, chose to fight (more on that soon).

MOVE TO ANN ARBOR

But the bust was only the beginning…in the months that followed, the TLE faced negative press, violent vandalism, and continued police persecution. Despite having a legal permit, their next big event — a “Love-In” on Belle Isle on April 30 — was raided by cops in riot gear.

“We were harassed 24/7,” said Sinclair. “Busted for incitement, obscenity, possession, whatever they could throw at us.”

The harassment only grew worse in the wake of the Detroit Riots in July, during which dozens of people were killed (mostly African-Americans, shot by law enforcement) and around 400 buildings were burned down. As a show of solidarity with the blacks being targeted, TLE hung a banner outside the commune that read “Burn, Baby, Burn!” — provoking riot police to once again raid the building.

As a result, the group eventually decided to do what many of the city’s citizens were doing—flee to the suburbs. In May 1968, TLE packed up, left Motor City, and relocated to a big house at 1510 Hill Street in the more liberal college town of Ann Arbor. There, TLE would regroup and launch a new, more political offshoot.

THE WHITE PANTHERS

After witnessing the police brutality against African-Americans during the Detroit Riots, Sinclair and his crew wanted to express solidarity with their black brothers and sisters, whose culture they greatly admired.

“We dug black people cos that’s where the great music came from and the great weed and the refreshing concepts of sexuality,” Sinclair once reportedly said. “All that stuff didn’t come from no white people.”

In the Fall of 1968, Plamondon showed Sinclair an interview with Black Panther Party co-founder Huey P. Newton in which he was asked what white people could do to support the Black Panthers and suggested they form their own organizations. So on November 1, John, Leni, and Pun declared the formation of a new radical-left political offshoot of Trans-Love Energies called the White Panther Party.

Conceived as a sort of hybrid of the Black Panthers and the Yippies, the group’s radical left, ten-point platform included an endorsement of the Black Panthers, free access to all basic human needs, demands for the end of war, money, and racial injustice, and the call for a “total assault on the culture by any means necessary, including rock and roll, dope and fucking in the streets.”

“I felt that we needed a combination of the discipline, organization, and ideology of the Black Panther Party, along with the theatrics and the media manipulation of the Yippies,” Plamondon said.

Within a year, over a dozen chapters of the White Panther Party had sprung up around the US and even in Europe. By 1970, the FBI reportedly considered the group “potentially the largest and most dangerous of revolutionary organizations in the United States.”

Though the White Panthers did not publicly advocate violence, both Sinclair and Plamondon (now the first hippie to be placed on the FBI’s ten most wanted list) were indicted as part of a conspiracy surrounding the bombing of a local CIA recruiting office in 1968. The charges were ultimately dropped, however, after it came out that WPP headquarters had been wiretapped without a warrant.

KICK OUT THE JAMS

Formed in 1964, the MC5 (originally Motor City 5) was a five-piece hard rock band from nearby Lincoln Park, Michigan. Sinclair first met the band in August 1966 after his release from DeHoCo when they were hired to play at an event held by the Detroit Artists Workshop in his honor called the Festival of People. Sharing similar political views, Sinclair immediately hit it off with the band — particularly lead singer Rob Tyner, as well as his best friend, an artist named Gary Grimshaw. Sinclair agreed to let them use the DAW as a rehearsal space, and before long, they asked him to be their manager.

Sinclair began booking them gigs around the area—most notably, as the new house band at Detroit's newly-opened Grande Ballroom, where they reportedly earned $125 a show opening for larger acts that came through town on tour. He also booked them to play a number of free live concerts in Ann Arbor’s West Park organized by the White Panther Party to help deliver their mission to the masses. In fact, the band became so intertwined with the Party that they even incorporated the Panthers' cartoon cat logo into their promotional artwork.

In the summer of 1968, the band played a number of shows along the East Coast. As part of that tour, Sinclair used his connection with Abbie Hoffman to book The Five a gig playing at the Yippies’ “Festival of Life” anti-war rally in Chicago’s Lincoln Park, just outside the Democratic National Convention. Originally planned to feature numerous national acts and host upwards of 100,000 people, Hoffman failed to secure permits for the event, and the MC5 ended up being the only band to perform to an audience of just a few thousand protestors in defiance of the city’s live music ban.

They only got to play a few songs before police moved in and began beating agitators with clubs, forcing the band to break down their gear and flee the scene. Before long, the rally erupted into a full-fledged riot—one that later caused to the Yippie leaders to be arrested (leading to the infamous Chicago 8 trial), and allegedly helped inspire (along with lots of weed and acid) Sinclair and the band to form the White Panther Party.

By that fall, the MC5 had signed with Electra Records, moved into Sinclair’s commune house in Ann Arbor, and recorded their first album, Kick Out the Jams, live at the Grande. Though originally promising to defend the band’s radical perspective, Electra reneged on that deal after their use of profanity and Sinclair’s liner notes caused a backlash among retailers—recalling the original pressing of the record and re-releasing a censored version without the notes or the iconic “motherfucker” in the title track’s opening line. Originally released in January 1969, the album sold over 100,000 copies and reached #30 on the Billboard 200 … nevertheless, the controversy caused the band to part ways with Electra. Soon after, they signed with Atlantic Records and, at the label’s advice, fired Sinclair in the summer of 1969.

TEN FOR TWO

In the two and a half years following his third cannabis arrest, Sinclair and his lawyers had been engaged in a protracted legal battle with the Michigan court system in an attempt to challenge the constitutionality of the state’s draconian drug laws— arguing that a) marijuana was not a narcotic, and b) that the mandated sentence of twenty years to life constituted “cruel and unusual punishment.” After numerous defeated motions, the case finally went to trial on July 22, 1969. By this point, the sales charge had been dropped, so he was only facing a simple possession charge. Three days later, the jury found him guilty after only an hour of deliberation...and on Monday, July 28, Sinclair —now 27 years old — was sentenced to a staggering 9.5-10 years, denied bail, and sent to Jackson State Prison.

Despite his lawyers’ ongoing efforts, Sinclair would spend the next two and half years behind bars (much of it in solitary since authorities at the prison found his influence on the other inmates disruptive).

WPP member David Fenton once noted that if Sinclair had simply abandoned his mission to challenge the government's classification of cannabis as an "addictive narcotic," he'd likely have been released far sooner.

“John could’ve gotten out of jail a lot earlier and could’ve avoided many, many, many months of abuse in prison and harrowing periods of solitary confinement," he said. "But … he wouldn’t compromise.”

While inside, he continued to coordinate with the WPP and penned two books: Guitar Army: Street Writings/Prison Writings (a collection of his writings for the underground press between 1968-71) and Music & Politics (co-authored by Robert Levin).

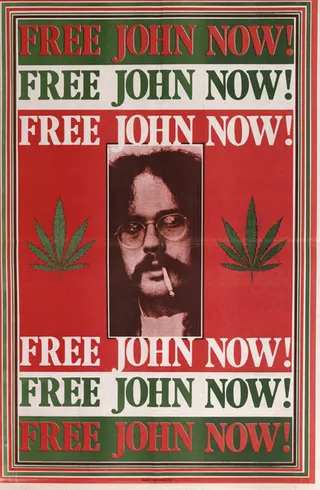

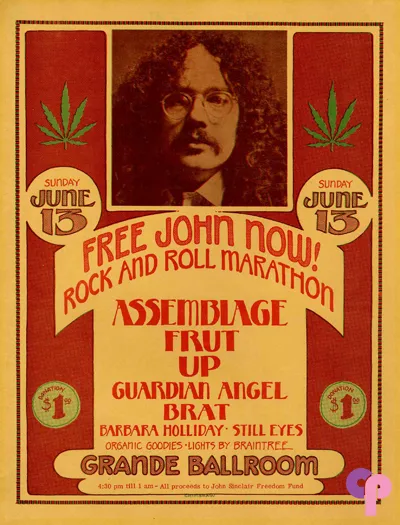

Sinclair's outrageous sentence made national headlines and galvanized the entire counterculture community under the rallying cry “Ten for Two” (ten years for two joints). Protests started popping up—not just in Ann Arbor and Detroit, but in other major cities as well. His wife Leni and brother David orchestrated a massive campaign to free him—organizing benefits and rallies, selling “Free John Now!” merch, sending letters to Congress with joints in them, and recruiting prominent activists and celebrities on John’s behalf.

Yippie leader Abbie Hoffman even famously stormed on stage at Woodstock between songs during The Who’s set to give an impromptu speech about Sinclair’s plight while allegedly tripping balls on White Lightning LSD, declaring, “I think this is a pile of shit while John Sinclair rots in prison!” before Pete Townsend hit him with his guitar and sent him packing, shouting “Get the fuck off my stage!”

Eventually, it would take the help of another British rock star—one far more famous and influential than Townsend— to spring Sinclair from the big house.

“FREE JOHN SINCLAIR” RALLY

After two-plus years of steadfast efforts by Sinclair’s wife, lawyers, and activist compadres, he still seemed no closer to being released from prison. So sometime in the summer of 1971, The Committee to Free John Sinclair decided they’d need to throw the biggest benefit yet to rally the entire counterculture community and apply pressure to powers that be. Leni and David were able to book the University of Michigan’s newly-built basketball venue, Crisler Arena, for December 10th.

They then enlisted a who’s-who of activist icons to speak (including Black Panther leader Bobby Seale and Yippies Allen Ginsberg, Jerry Rubin, and Ed Sanders) and booked a solid lineup of musical acts to perform, including jazz legend Archie Shepp, folk singer Phil Ochs, rockers Commander Cody and Bob Seger, and Motown sensation Stevie Wonder (who was unannounced).

But their real ace in the hole was none other than former Beatle himself, John Lennon, who — after reading Sanders’ poem “The Entrapment of John Sinclair” in the Free Press and speaking with Sanders and Rubin — agreed to come headline the event with his wife Yoko Ono for free.

That fall, Leni and producer Peter Andrews flew to New York, where they met with John and Yoko to formalize the deal.

“I had Lennon sign a contract for $500 to appear, and he crossed it out and put, ‘To be donated to the John Sinclair Freedom Fund.’”

Much to their surprise and delight, Lennon had also written a song about Sinclair (titled simply "John Sinclair") to perform at the rally (later released on his Some Time in New York City album), which he premiered for them live. (Sinclair would hear the song shortly after when one of his lawyers played it for him during a visit to the prison.)

Feeling that the contract wouldn’t be enough to convince people that Lennon was actually coming, he also got John to agree to record an audio message as verification before leaving.

“Hello, this is John with Yoko here. I just want to say we’re coming along to the John Sinclair bust fund rally to say hello. I won’t be bringing a band or nothing like that because I’m only here as a tourist, but I’ll probably fetch me guitar, and I know we have a song that we wrote for John [Sinclair]. So that’s that.”

The Committee to Free John Sinclair played that recording at a press conference in Ann Arbor two days before the event, and that was all it took — tickets went on sale that day and sold out in less than three hours.

“It was like God was coming to Ann Arbor,” Fenton recalled. “It was amazing. I remember announcing it on the radio, and people were so excited.”

“(Lennon) just put it over the top,” Sinclair later said. “It was the fastest-selling ticket in Michigan pop music history, and that just put the focus on my case and the issue.”

That Friday night, 15,000 plus attendees packed into the Crisler for eight hours of activism and entertainment, highlights of which included Stevie Wonder’s surprise set (which, according to Andrews, Lennon “flipped” over) and an emotional phone call by Sinclair himself from prison that was piped over the PA during which he got to hear the capacity crowd all chanting “Free John! Free John!”

Naturally, the FBI had undercover agents trawling through the crowd, taking notes, but other than that, law enforcement was pretty relaxed…especially regarding the thick fog of marijuana smoke that filled the arena.

“I remember all these people breaking out literally pounds of pot in the audience,” Fenton said.

NORML founder Keith Stroup, who attended the show, later recounted:

“It became quickly apparent that marijuana was effectively legal in Crisler Arena that evening. People were not only smoking joints openly and passing them around, but several people, including one sitting near my seat, had quantities of marijuana sitting open on their laps, freely rolling joint after joint to make sure everyone who attended could get high for the occasion. It was the first time I recall ever seeing such mass civil disobedience, and it was empowering to experience. Tens of thousands of people openly smoking marijuana and no one being hassled by the police. Clearly, someone had made the decision that it was better to allow these radicals to smoke at this event than to attempt to arrest such a throng.”

Then, of course, there was Lennon’s finale — his first live performance since the Beatles broke up. Finally taking the stage at 3 am, Lennon addressed the crowd:

“We came here not only to help John [Sinclair] and to spotlight what’s going on, but also to show and to say to all of you that apathy isn’t it, and that we can do something. Okay, so Flower Power didn’t work. So what? We start again.”

He and Yoko then performed a 15-minute, four-song acoustic set, backed by their Yippie pals David Peel and the Lower East Side band—closing out the show with John Sinclair’s eponymous new anthem:

“It ain't fair, John Sinclair / In the stir for breathin' air… They gave him ten for two / And what else can the judges do? / They gotta, gotta, gotta, gotta … set him free.”

Three days later, on December 13, authorities did just that.

“On Monday morning, my lawyers informed me that I would be released on appeal bond by the end of the day," Sinclair remembered, "and at 8:30 pm, I stepped out from behind the iron bars and into the arms of my family and friends.”

As it so happens, just one day before the rally, the Michigan Legislature had passed a bill that excluded marijuana from the state’s narcotics code and drastically reduced the penalties associated with cannabis from a maximum sentence of ten years to just 90 days. Given this development and the 29 months he’d already served, the State Supreme Court had ordered Sinclair to be set free pending the outcome of his appeal. Three months later, in March 1972, the court granted his appeal, overturned his conviction, and declared the state’s marijuana laws unconstitutional. He fought the law … and he won.

How much influence did Lennon’s presence at the rally exert over the state legislature and Supreme Court’s decisions? It’s difficult to say …but as far as Sinclair was concerned, it made all the difference.

“I was saved by John Lennon … not too many people can say that,” Sinclair once said. “They had to deal with the fact that John Lennon was coming there to oppose their view. That was like a bombshell. That’s what really put the ultimate pressure on the state legislature when they were considering this law. Don’t fuck with a Beatle.”

Sadly though, the Feds would indeed fuck with that Beatle. Thanks in part to his involvement with the rally, the FBI began surveilling Lennon and four months later initiated deportation proceedings against him — a protracted legal battle that didn’t end until Nixon’s resignation in 1975.

MICHIGAN MARIJUANA REFORM

With Michigan’s old cannabis laws struck down by their Supreme Court in early March 1972, and the new, more lenient law they’d passed in December not going into effect until April 1, that meant that during that interim, there were no cannabis prohibition laws on the books. So technically, thanks to Sinclair, marijuana was effectively legal in the state of Michigan for about three weeks.

To both celebrate this victory and protest the new penalties being adopted, Sinclair helped organize a smoke-in of sorts at “The Diag” on the University of Michigan campus in Ann Arbor at high noon on the Saturday the new law was going into effect — April Fool’s Day. Several hundred stoners blazed up publicly “to let them know that we’d still be smoking even though they were putting this law back in,” Sinclair stated. Originally referred to as simply the “Hash Festival,” that rally — later renamed Hash Bash — has been held on the first Saturday of April every year since to this day.

During his two-year incarceration, Sinclair’s communal collective evolved once again: turns out, the name “White Panther Party” sounded to some like a white supremacist organization — the very opposite of the group’s purpose. As a result, the Panthers disbanded by 1971 and reconstituted as the community-oriented Rainbow People’s Party and the more politically oriented Human Rights Party (HRP).

The following year, the HRP got two candidates elected to the City Council, enabling them to pass an ordinance on May 15, 1972, making marijuana possession a civil offense carrying just a $5 fine and making Ann Arbor the first city in the nation to decriminalize Cannabis.

LATER YEARS

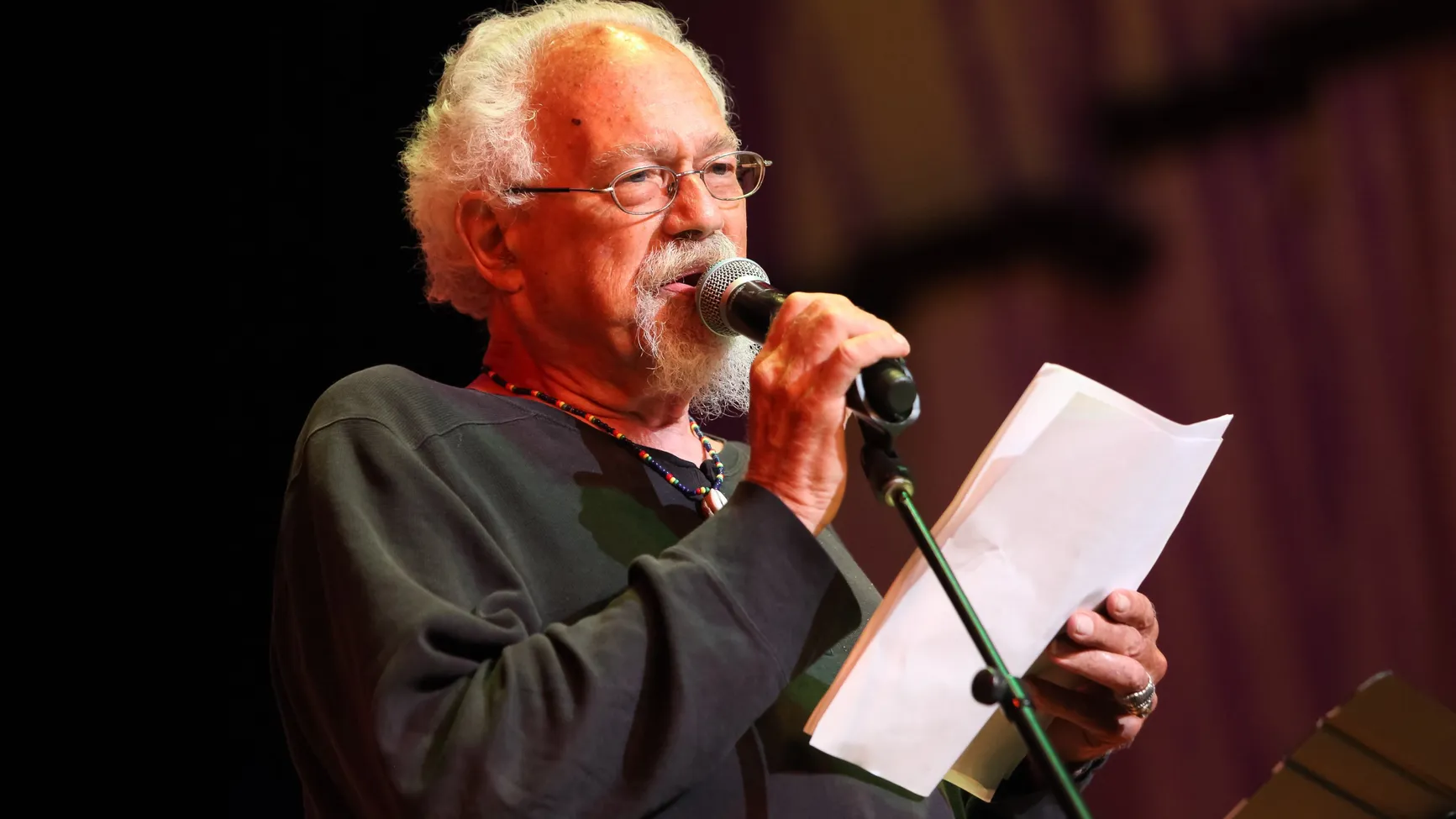

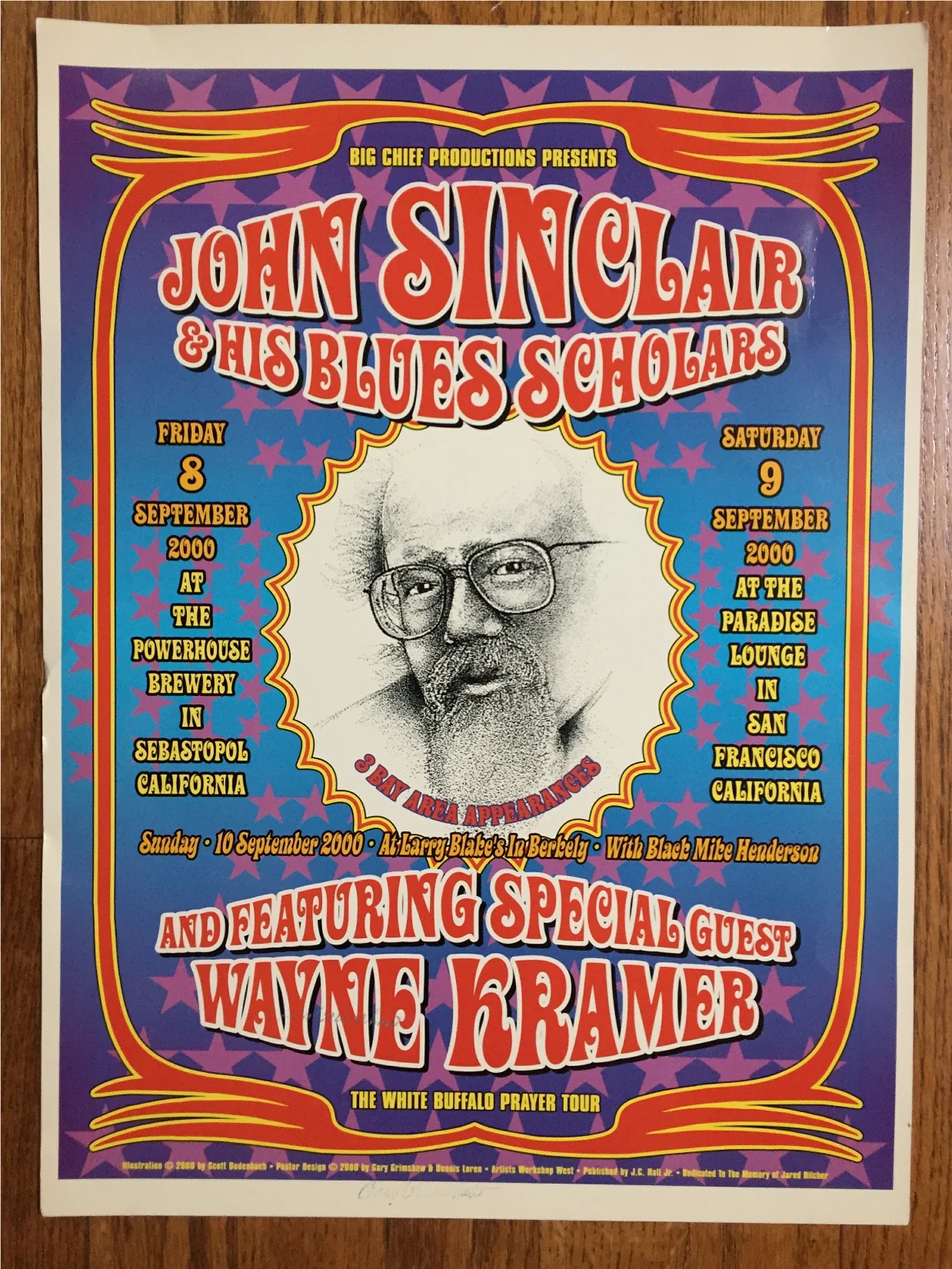

After successfully reforming Michigan’s marijuana laws and the subsequent dissolution of his various organizations, Sinclair retired from political activism and shifted focus back to artistic pursuits. During the '80s, he moved back to Detroit, where he served as editor of City Arts Quarterly and hosted a radio show at WDET. Later, in 1991, he moved to New Orleans, where he spent 12 years at WWOZ and was voted the city’s most popular DJ for five consecutive years in a row. He also wrote for various music publications and formed his band, John Sinclair and His Blues Scholars — performing spoken word poetry over blues and jazz music.

From 2003 to 2008, Sinclair lived in Amsterdam, where he launched Radio Free Amsterdam (an online “podcast” network before podcasts were a thing) and broadcasted his weekly program, the John Sinclair Music Show, live from the 420 Café. He also created The John Sinclair Foundation, a non-profit dedicated to preserving his artistic legacy; over the decades, Sinclair released more than 20 albums and wrote numerous books, essays, and articles, including the long-running cannabis column “Free the Weed” and the seminal pro-pot manifesto Marijuana Revolution.

Sinclair moved back to Detroit in 2008, where he became a professor of Blues History at Wayne State University, opened the John Sinclair Foundation Café (a happening hangout for hippies and hipsters) at Detroit's Psychedelic Shack in 2018, and became the first person in Michigan to purchase weed legally in December 2019. Despite his declining health, he remained a revered figurehead, appearing and speaking at the Hash Bash rally each year.

Over his lifetime, Sinclair had several documentaries made about him and was honored with numerous awards and accolades, including the Lester Grinspoon Lifetime Achievement Award by High Times in 2011 and a 420 Icon award that we were honored to bestow upon him on April 20, 2020, during our historic live stream event.

John Sinclair died of congestive heart failure at the Detroit Receiving Hospital on the morning of Tuesday, April 2, 2024. He was 82.

John Sinclair was one of the all-time greatest icons of cannabis culture — a true legend whose memory and legacy will blaze on for eternity.

Comments