HASHISTORY - PART 1: FROM PERSIA TO PARIS

- Bobby Black

- Jul 10, 2021

- 13 min read

Updated: Jul 11, 2021

When it comes to the history of hashish, the facts are as fascinating as the folklore.

Archeological and anthropological evidence proves that the cannabis plant has been used by humanity for thousands of years as a source of food, medicine, and sacrament. But what about the plant’s collected resin, better known as hashish? What follows is our best attempt to sort through the myths and mysteries and piece together an accurate account of hash’s hazy history.

ISLAMIC ORIGINS

It’s commonly believed that the word hashish derives from the Arabic root word hasis, meaning dried grass or herb. The very first form of hashish was undoubtedly charas—the sticky, resinous residue that accumulates on one's hands when handling cannabis flowers, which is then collected and pressed into a ball or block. Prehistoric Homo erectus and Homo sapiens would have surely encountered this while gathering, harvesting, and processing the plant, and likely would’ve scraped it off and tasted it, discovering its mildly medicinal and mind-altering effects.

The first historical records of hashish date back to the “Golden Age of Islam” in ancient Persia—sometime between the writing of the Koran in 632 and around 900 CE. Unlike alcohol, which was forbidden by the Koran as a khmar (intoxicant), cannabis was originally considered a medicine and therefore not included in the prohibition. The earliest written reference to hashish appears to be in The Book of Poisons—a toxicology/astrology treatise by Iraqi alchemist Ibn Wahshiyya published in the 10th century. In it, Wahshiyya refers to a toxic concoction consisting of cannabis extract and other aromatic herbs, which he claimed was lethal when inhaled.

Another, more famous text from that period in which hashish is mentioned is the fabled 1001 Arabian Nights, which even includes a story entitled “The Tale of the Hashish Eater.”

THE SUFI

The earliest Muslim group known to have embraced hashish was the Sufis— a mystical sect of Islam devoted to communion with God through deep introspection that arose sometime during the 8th century. Once referred to as “the hippies of the Arab world,” Sufi monks believed that the elevation of consciousness hashish provided could assist them along the path to enlightenment. For them, eating hashish was, according to one Muslim critic, “an act of worship.”

One Sufi legend even claimed that it was the founder of one of its sects (a group of dervishes into piercings called the Haydariyya), an ascetic monk named Shayk Haydar, who first discovered hashish. According to the story, after ten years of reclusivity in his mountaintop monastery, Haydar ventured into the desert, where he discovered a “sparkling” plant and ate it. He returned to the monastery in a euphoric state, shared the plant’s magical properties with his fellow monks, then swore them to secrecy about it, saying: "God almighty has granted you as a special favour an awareness of the virtues of this leaf, so that your use of it will dissipate the cares that obscure your souls and free your spirits from everything that might hamper them, keep carefully, then the deposit he has confided in you."

After his death in 1221, Haydar was even buried with cannabis leaves and seeds. But despite the evidence confirming Haydar’s love of cannabis in general, there isn’t any actual proof that he made or used hashish. Regardless, both Arabic and Western scholars agree that the Sufis did eventually embrace hashish as a sacrament and helped spread its use throughout the lower and middle-class populations of Iraq, Syria, and Egypt.

THE HASHASHIN

Though cannabis resin was referenced in texts since the 9th century, the word hashish itself wasn’t reportedly seen in print until 1123 CE, when it was used in an Egyptian pamphlet accusing a sect of Muslims called the Nazari of being “hashish-eaters.” Not unlike the Sufi, the Nazari were a progressive, somewhat mystical sect from the Ismaili branch of Shia Islam founded in 1090 that emphasized rationality and social tolerance.

The Nazari were based in a mountaintop fortress in northern Iran called Alamut Castle (Alamut meaning "eagle's nest") and were ruled over by the group’s founder, Hassan-i Sabbah—a.k.a. “The Old Man of the Mountain.”

Since he had no army, Sabbah created an elite squadron of ninja-like warrior spies known as the Fidai (from fidayeen, meaning “martyrs”). Rather than engaging them in traditional battles, Sabbah sent the Fidai out to execute espionage missions and covert murders of their enemies. The Fidai were reportedly so devoted to their Imam and their faith that they would gladly sacrifice their lives upon his command. For this reason, many consider the Fidai the precursors of modern-day suicide bombers, or the first jihadi-style terrorists.

According to legend, the way that Sabbah brainwashed these fanatical fighters into such devotion was through the use of a mind-altering concoction that purportedly contained hashish. It’s from this legend that it was believed the Fidai were eventually ascribed their notorious nickname: hashashin (Arabic for “hashish eaters”), from which we derive the modern word “assassin.”

The true etymology of that moniker, however, is far from clear. Some believe the name was actually derived from the word assasyun (from the Arabic root assas, meaning "base" or foundation), meaning "people who are true to the foundation of the faith"—or in other words, fundamentalists. This interpretation would certainly make sense, considering fundamentalists are typically the kind of people most enthusiastic about sacrificing their lives for their religion. Others say it comes from the Persian word hassasin, meaning “herb seller” or “healer,” while still others say it may simply mean “followers of Hassan.”

What’s more, even if the nickname did originate from the term “hashish-eaters,” that still doesn’t verify the veracity of the legend. At that time, calling someone a “hashish eater” had a broader connotation beyond its literal meaning: it was a derogatory term used to denote undesirable, low-class people in general. Therefore, it’s entirely possible that the name was only ascribed to them by other Muslim groups as a way to express contempt for them rather than being based on actual evidence of their hash use. Because in reality, no actual evidence was ever discovered or documented showing that the Fidai made or consumed hashish. Nevertheless, the false legend stuck—thanks almost entirely to the teachings of two men, the first of which was famed Italian explorer Marco Polo.

MARCO POLO

It was through his wildly popular book The Travels of Marco Polo, published around 1300, that Polo introduced the Western world to the legend of the Hashashin. In it, Polo recounts second-hand the unverified tales he’d heard of the Old Man of the Mountain and his indoctrination methods:

“He had caused a certain valley between two mountains to be enclosed, and had turned it into a garden, the largest and most beautiful that ever was seen, filled with every variety of fruit. In it were erected pavilions and palaces the most elegant that can be imagined, all covered with gilding and exquisite painting. And there were runnels too, flowing freely with wine and milk and honey and water; and numbers of ladies and of the most beautiful damsels in the world, who could play on all manner of instruments, and sung most sweetly, and danced in a manner that it was charming to behold. For the Old Man desired to make his people believe that this was actually Paradise. So he had fashioned it after the description that Mahommet gave of his Paradise, to wit, that it should be a beautiful garden running with conduits of wine and milk and honey and water, and full of lovely women for the delectation of all its inmates. And sure enough the Saracens of those parts believed that it was Paradise!”

“Now no man was allowed to enter the Garden save those whom he intended to be his ASHISHIN. There was a Fortress at the entrance to the Garden, strong enough to resist all the world, and there was no other way to get in. He kept at his Court a number of the youths of the country, from 12 to 20 years of age, such as had a taste for soldiering, and to these he used to tell tales about Paradise, just as Mahommet had been wont to do, and they believed in him just as the Saracens believe in Mahommet. Then he would introduce them into his garden, some four, or six, or ten at a time, having first made them drink a certain potion which cast them into a deep sleep, and then causing them to be lifted and carried in. So when they awoke, they found themselves in the Garden.”

“And when he wanted one of his Ashishin to send on any mission, he would cause that potion whereof I spoke to be given to one of the youths in the garden, and then had him carried into his Palace. So when the young man awoke, he found himself in the Castle, and no longer in that Paradise; whereat he was not over well pleased. He was then conducted to the Old Man's presence, and bowed before him with great veneration as believing himself to be in the presence of a true Prophet. The Prince would then ask whence he came, and he would reply that he came from Paradise! and that it was exactly such as Mahommet had described it in the Law. This of course gave the others who stood by, and who had not been admitted, the greatest desire to enter therein.”

Though many at the time believed the “intoxicating potion” Sabbah used to convert his followers into bloodthirsty killers to be a form of hashish wine, Polo never explicitly mentions hashish in the book. It wasn’t until five centuries later that the false association between the Fidai and hashish would be presented to the world as “fact,” thanks to the second man responsible for perpetuating the legend—a French linguist and “Orientalist” named Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy (more on him later).

Regardless of the nickname’s true origin, one thing is not disputed: the Hashashin were feared and reviled, and it seems likely their enemies fabricated these fictions as a way to either discredit them or explain away their victories.

Sabbah died in 1124, but his Order of Assassins continued to terrorize Christian Crusaders, Sunni caliphs, and various other enemies across the Middle East for another century before ultimately being brought down by the infamous conqueror Genghis Khan, whose armies invaded Alamut and decimated the cult in 1256.

Though the Mongols may have killed off the Hashashin, however, they did nothing to kill the appeal of hashish; in fact, some Arab historians credit the Mongol invasions for it’s spread during the 13th century. As the Mongols invaded Muslim territories and drove refugees (many of whom were Sufis) westward into Iraq, Syria, and Egypt, they brought cannabis and hashish with them.

INTO EGYPT

The first record of hashish use in Egypt comes to us from a Spanish-born Muslim botanist by the name of Ibn al-Bayṭar al-Malaqi, who in 1227 observed Egyptian Sufis (known as fakirs) rolling charas into small balls and swallowing them in the nation’s capital of Cairo. There was a park there known as the Gardens of Kafur where the Sufi and other poor hash-heads would congregate, grow their cannabis, and make and consume hashish—that is, until 1266 when King al-Zahir Babar decreed hashish to be illegal in the city, destroyed the gardens and threatened anyone caught with it with prison and “de-teething.”

Eventually, due to concern about the moral and societal decline attributed to the drug, Sunni religious authorities took action to curb its spread: officially expanding the interpretation of khmar to include cannabis and hashish and essentially condemning the Sufi as heretics. By the beginning of the 15th century, Sunni officials had declared hashish illegal under Islamic law, an offense punishable by up to 80 lashes. Regardless of these attempts to suppress it, thanks to the teachings of the Sufis, the conquests of the Mongols, and the traders and explorers traveling along the old Silk Road, hashish use continued to expand throughout the known world. By the end of the 13th century it had spread throughout Afghanistan, Russia, and the rest of Central Asia; by the end of the 14th century, it had extended into Eastern and Northern Africa, and up into Spain.

Until this point, the predominant method of consuming hashish had always been eating it or breathing it in along with other herbs and spices in the burning of incense. It’s not clear exactly when smoking it started becoming the preferred method of ingestion, but it's believed to be sometime in the 16th century—around the same time that tobacco was brought back to Eurasia from the New World, as the practice of mixing it with tobacco in pipes or cigarettes may have helped spur hash’s popularity in Europe (a practice that is still widespread in European countries today).

This increased demand is also credited by some as the impetus behind a new technique for making hashish that was likely developed in Afghanistan sometime in the 17th century: dry sieving. By sifting the dried resin glands out of the plant using screens rather than collecting it on the hands from live plants, one could produce more hash in less time. Nepalese charas and Afghani dry sift became hot commodities along the spice routes from Asia during this time...but it wasn’t until the 18th century that hashish would really make its mark on Europe, courtesy of another infamous conqueror.

ENTRÉE FRANCE

In 1798, France’s aspiring emperor Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Egypt. Since alcohol was banned in the Muslim country, his 35,000 troops had no access to the wine they were so accustomed to and instead adopted hashish as their self-medicating intoxicant of choice. Hashish consumption among French troops became such a widespread problem that on October 8, 1800, French General in Chief Jacques-François “Abdallah" Menou (with the support of the Sunni elite, who despised the lower-class Shi’ites) issued a decree banning cannabis and hashish across Egypt—ordering all cafes that sold it to be closed and imposing hefty fines and imprisonment on anyone using, selling or producing it (considered by some as the first drug prohibition law of the modern era). But naturally, much like America’s eventual War on Drugs, his prohibition failed. And when Anglo-Ottoman forces drove out the French troops in 1801, they brought their hash back home with them.

By that time, most French citizens had heard of hashish, thanks to Antoine Galland's translation of The 1001 Arabian Nights published a century earlier. The stories sparked a romantic fascination with hashish in France’s collective imagination. Over the next two centuries, that love affair grew—igniting a new craze that soon spread across Europe, and helped fuel an explosion of creativity and medical research, both of which were exemplified by Paris’ infamous Club des Hashischins.

LES CLUB DE HASHISCHINS

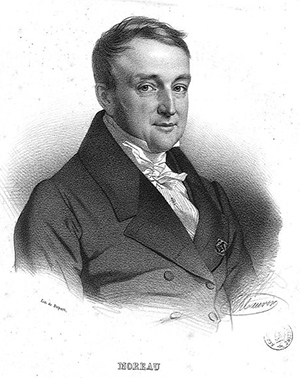

Hashish wasn’t the only thing growing in popularity in nineteenth-century France—it was also one of the birthplaces of modern psychiatry. Early psychiatrists known as “alienists” were desperate to unlock the secrets of the human mind—to understand and treat various forms of mental illness. One such alienist was a man named Dr. Jacques-Joseph Moreau. Moreau had first tried cannabis in 1840 in Egypt out of scientific curiosity, after hearing of its therapeutic effects during a four-year trip to the Orient. He quickly realized, however, that its intoxicating effects would interfere with his ability to objectively assess the substance; to properly study it, he determined, he’d need guinea pigs to observe. For that, he turned to a new friend who had expressed interest in the drug: journalist and philosopher Théophile Gautier. So in 1844, the duo founded the Club des Hashischins—a private social club in Paris where the literary, artistic, and intellectual elite of the day would gather to get high.

The group held monthly meetings called “séances” (not the kind with the ghosts, though they certainly may have hallucinated some) at a gothic hotel called Pimodan House (later known as Hotel de Lauzun). There, in the rooms of painter /musician Fernand Boissard, the club held private hashish rituals, in which they’d dress in Arabic attire, feast, and ingest a green paste called dawamesk made with butter, sugar, nuts (typically pistachio), spices (cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg), and of course, lots of hashish. The dawamesk would be doled out by Moreau in thumb-sized doses on gold and silver spoons, then ingested along with a meal or blended into strong Arabic coffee. They would then proceed to talk, laugh, eat, drink, and hallucinate together, while Moreau took notes.

Among the prominent intelligentsia that boasted membership in this club were authors Honoré de Balzac, Charles Baudelaire, Alexandre Dumas, and Victor Hugo—many of whom went on to write about their experiences.

In Dumas’ famous 1844 revenge novel The Count of Monte Cristo, the title character himself is a hashish eater—popping pills comprised of hash and opium, and offering a guest some dawamesk jam:

“That kind of green preserve is nothing less than the ambrosia which Hebe served at the table of Jupiter! … Taste this and the boundaries of possibility disappear… Taste this, and in an hour you will be a king…”

At these words he uncovered the small cup which contained the substance so lauded, took a teaspoonful of the magic sweetmeat, raised it to his lips and swallowed it slowly, with his eyes half shut and his head bent backward…

“Did you ever hear… of the Old Man of the Mountain, who attempted to assassinate Philippe Augustus?”

“Of course, I have.”

“Well, you know he … gave them to eat a certain herb, which transported them to paradise…

“Then,” cried Franz, “it is hashish! I know that—by name at least.”

“That is it precisely, Signor Aladdin; it is hashish—the purest and most unadulterated hashish of Alexandria...’”

Though he typically abstained from indulging, Balzac finally succumbed to curiosity sometime in 1845, after which he claimed to hear “celestial voices” and see “visions of divine paintings.”

Despite being known for his debaucherous habits, Baudelaire also apparently did not care much for hash; According to Gautier, he famously said, "wine makes men happy and sociable; hashish isolates them. Wine exalts the will; hashish annihilates it." Thus, though Baudelaire attended the séances regularly, and once referred to dawamesk as “the playground of the seraphim,” he reportedly only indulged a few times. Nevertheless, his 1860 work about drugs entitled Les Paradis Artificiels (The Artificial Paradise) included a section entitled “The Poem of Hashish” (which was actually an essay, not a poem), in which he writes:

"Among the drugs most efficient in creating what I call the artificial ideal…the two most energetic substances, the most convenient and the most handy, are hashish and opium."

He goes on the describe hashish’s effects in great detail:

"At first, a certain absurd, irresistible hilarity overcomes you… Next your senses become extraordinarily keen and acute. Your sight is infinite. Your ear can discern the slightest perceptible sound, even through the shrillest of noises. The slightest ambiguities, the most inexplicable transpositions of ideas take place. In sounds there is colour; in colours there is a music... You are sitting and smoking; you believe that you are sitting in your pipe, and that your pipe is smoking you; you are exhaling yourself in bluish clouds. This fantasy goes on for an eternity. A lucid interval, and a great expenditure of effort, permit you to look at the clock. The eternity turns out to have been only a minute. The third phase... is something beyond description. It is what the Orientals call 'kef'—it is complete happiness. There is nothing whirling and tumultuous about it. It is a calm and placid beatitude. Every philosophical problem is resolved. Every difficult question that presents a point of contention for theologians, and brings despair to thoughtful men, becomes clear and transparent. Every contradiction is reconciled. Man has surpassed the gods."

In 1845, after a year of attending the club’s séances, Moreau published the results of his observations—the first scientific, psychiatric work on the effects of hashish on the human mind entitled Du Hachisch et de l'Alienation Mentale - Études Psychologiques (Hashish and Mental Illness - Psychological Studies). In it, he postulated that the effects of hashish essentially reproduced the symptoms of mental illness, which he identified as, among other things, a loss of ability to control one’s thoughts, accurately judge time, and discern between truth and falsehood.

Though Moreau’s observations of the group ended in 1846, the Club de Hashischins continued to convene for a few more years, until it was ultimately dissolved in 1849.

COMING SOON: PART 2!

To hear more about the history of hashish listen to Episode 13 of our Cannthropology podcast featuring master hash maker Frenchy Cannoli.

Не так давно, я почав більше часу приділяти новинам, що в свою чергу дуже сильно вплинуло на моє сприйняття подій та загалом на те, як ці події аналізувати. Хочу подякувати новинному порталу Glavcom за те, що вони роблять такий якісний та актуальний матеріал, котрий допомагає читачам бути завжди в курсі подій. Окреме дякую хочу сказати за те, що вони пишуть подробиці про військову допомогу, про ту роботу та публікує матеріали з інтерв'ю за участі тих, кому ця допомога надійшла, це неаби як курто. Загалом, якщо брати саме військову допомогу https://glavcom.ua/tags/vijskova-dopomoha.html, то для мене більш за все важливо те, щоб наші хлопці отримували її вчасно та були максимально в безпеці. Та кажучи про роботу новинного порталу, я хочу наголосити на тому,…